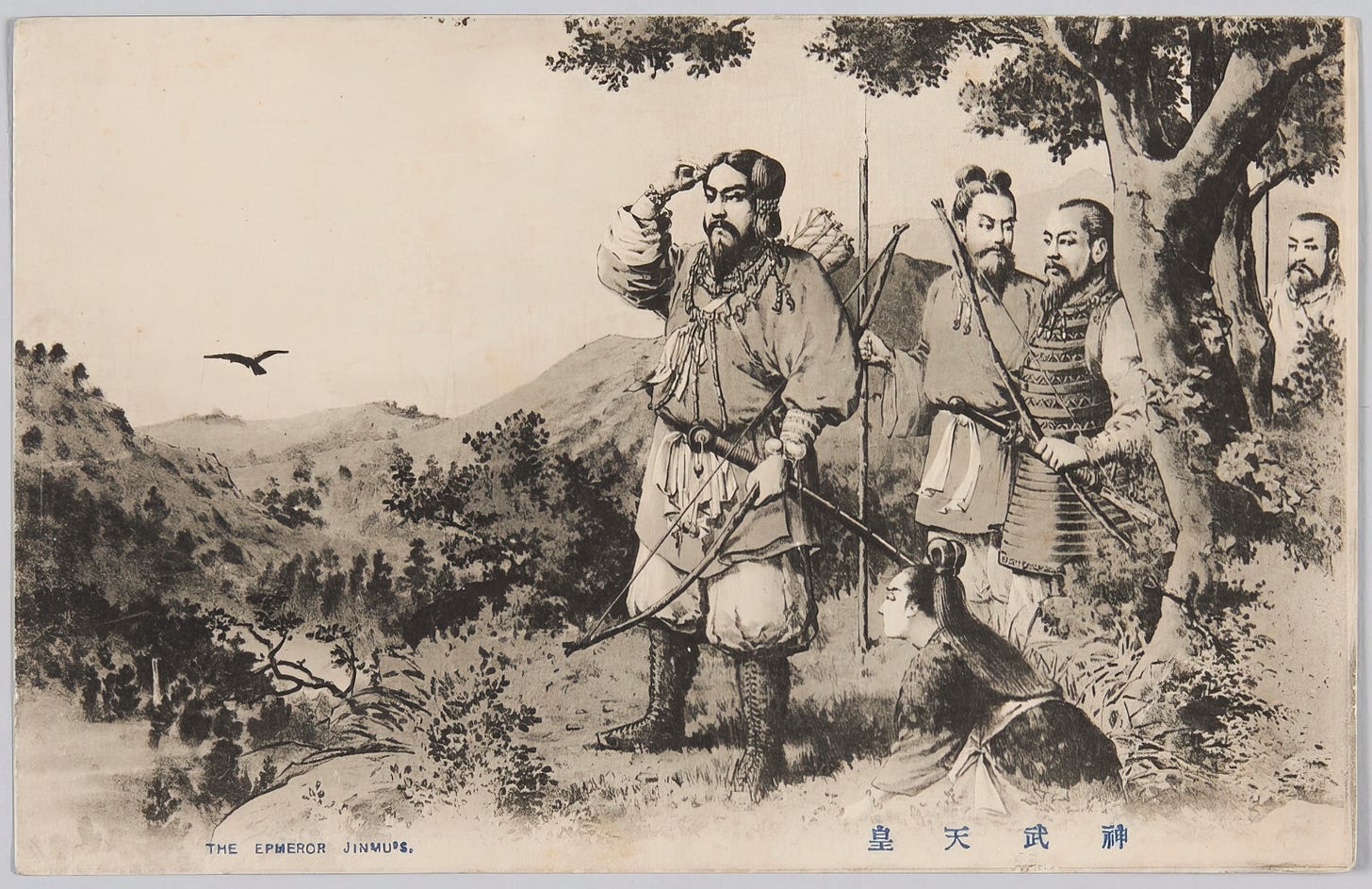

Did Emperor Jimmu Really Rule Japan in 660 BCE?

The Political and Astronomical Roots of the 660 BCE Narrative

Today, I’ll offer further insights into the widely accepted theory of Emperor Jimmu’s accession in 660 BCE, a date that has served as the foundation for the ideology of Japan’s unbroken imperial lineage (bansei ikkei). While previously accepted as historical truth, recent scholarship increasingly questions the authenticity and accuracy of this timeline.

In my last article, I proposed that the concept of an unbroken imperial lineage—long central to Japan’s national identity—was not grounded in historical fact but was rather a modern ideological construction. Now, let’s delve deeper into the origins of the legendary date of 660 BCE and understand the complex historical and political forces that shaped it.

Historically, the first official claim of Emperor Jimmu’s ascension to the throne dates to 660 BCE, as recorded in the Nihon Shoki (720 CE). However, this specific date lacks archaeological and historical verification and appears instead to be an artificially calculated date influenced heavily by imported Chinese astronomical methods.

The advanced calendrical techniques required to compute such ancient dates only reached Japan around 602 CE, brought by monks from the Korean kingdom of Baekje. This strongly suggests that Emperor Jimmu’s accession date was not a historical memory from ancient Japan but rather a politically motivated calculation undertaken in the early 7th century.

At the heart of this calculation stood Empress Suiko (r. 593–628), Japan’s 33rd emperor, who, despite officially ruling, served largely as a figurehead. Actual power rested with her influential regents, Soga no Umako and Prince Shōtoku. This political triumvirate was pivotal in Japan’s first major wave of Sinicization, including Buddhism’s introduction and the widespread adoption of Chinese administrative and calendrical techniques.

Particularly compelling to this ruling elite was China’s imperial system, wherein historical chronicles legitimized dynastic rule through precise calendrical records. Inspired by this method—exemplified notably in Sima Qian’s Records of the Grand Historian (Shiji)—the Suiko-Soga-Shōtoku trio initiated Japan’s earliest state-sponsored historical writing projects, employing immigrant scholars from China and the Korean Peninsula who possessed sophisticated calendrical knowledge.

It was within this context that the legendary date of Emperor Jimmu’s ascension—660 BCE—was first systematically calculated. According to the Nihon Shoki, Emperor Jimmu’s accession aligned with the “Xin-you (辛酉)” calendrical cycle, a critical reference point for subsequent dating methods.

However, the precise numerical date of 660 BCE was not fully solidified until the Meiji Restoration. In 1872, when Japan formally adopted the Western Gregorian calendar, the imperial chronology underwent significant revision. Previously used lunar-solar calendar dates were recalibrated, definitively establishing Emperor Jimmu’s accession year as 660 BCE within a Western calendrical framework.

Yet, the process of translating Japan’s historical lunar-solar calendar into a Western-style chronological system began much earlier, with key intellectual contributions from two prominent Edo-period figures:

• Arai Hakuseki (1657–1725), a renowned Confucian scholar who served the Tokugawa shogunate. Hakuseki authored Seiyō Kibun (Western Records), drawing upon Western scientific knowledge acquired through Dutch merchants at Nagasaki. He may have been among the first to propose Emperor Jimmu’s accession date as precisely 660 BCE based on these imported methods.

• Kamo no Mabuchi (1697–1769), an influential scholar of Kokugaku (National Learning). Though details remain unclear, Mabuchi likely reinforced the acceptance of the 660 BCE date, possibly influenced by Hakuseki’s earlier conclusions. His broad scholarly influence further entrenched this theory within national historical consciousness.

By the late 19th century, amid surging nationalism, this calculated date became enshrined as historical truth, reinforcing the ideology of Japan’s uninterrupted imperial lineage. This narrative profoundly influenced Japan’s identity well into the prewar period, creating a powerful mythology around the imperial institution.

Yet before World War II, a pioneering historian emerged, boldly arguing that the 660 BCE date lacked historical authenticity, suggesting instead that it resulted directly from imported Chinese astronomical calculations rather than genuine historical memory. In my next article, I’ll examine this groundbreaking scholar’s contributions, highlighting how their work challenged—and forever reshaped—Japan’s historical narrative.