Kojiki’s Creation and the Political Struggles Behind Japan’s Oldest Chronicle

Power Struggles and Their Influence on the Writing of Kojiki

Today, I will be discussing the circumstances surrounding the compilation of Japan’s oldest text, the Kojiki.

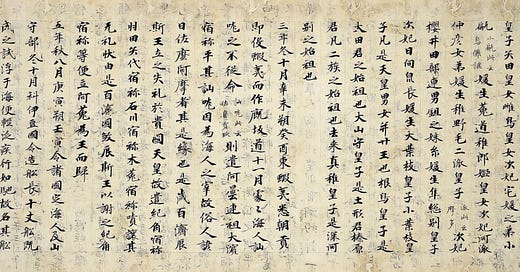

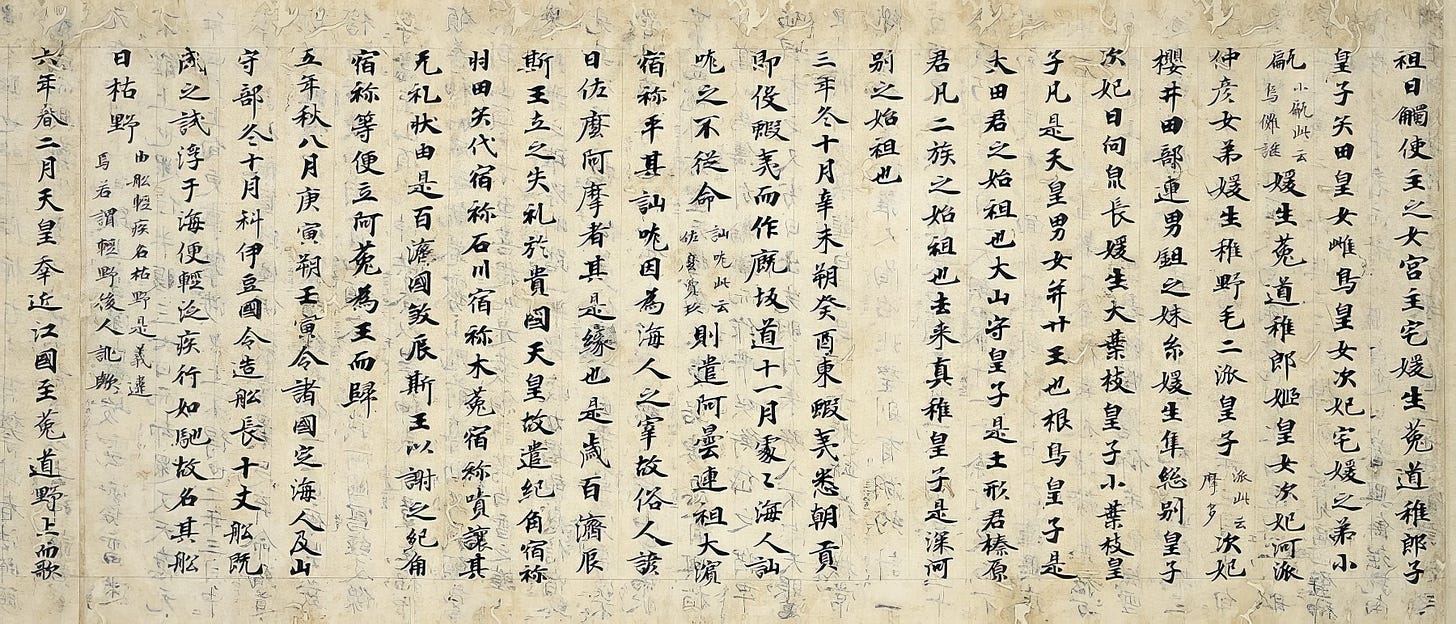

Readers may not be familiar with it, but the Kojiki, compiled in 712, is Japan’s oldest recorded text. It consists of two major parts: the Age of the Kami section and the Age of Emperors section.

The former deals with mythological narratives, while the latter is compiled based on ancient historical processes. However, the Kojiki’s essential character lies in its advanced techniques of compiling ancient traditions, whereas a more historically record-oriented character is found in the Nihon Shoki (completed in 720), another ancient text.

Still, “the oldest in Japan” only takes us back to the 8th century. The 8th century in Japanese history was a complex era during which Buddhism, already influenced by Sinicization, had been transmitted through the Korean peninsula, undergoing various twists and turns.

For a long time, political power resided in the old Shinto-affiliated establishment. They clashed with a new faction that aimed to promote Buddhism, which had been introduced by immigrant groups. This power struggle sparked many conflicts. The old faction was represented by the Mononobe clan, the new faction by the Soga clan.

Ultimately, the old powers could not resist the new tides of the era and were defeated. Soga no Umako (551–626), the head of the Soga clan who seized the new political authority, is said to have burned the archives owned by the Mononobe clan, effectively erasing the previous historical records.

In the Mononobe archives, numerous texts were stored, including those written in the languages of diverse peoples who had migrated to ancient Japan. By eradicating these documents, the Soga succeeded in dramatically advancing the promotion of Buddhism. Among the burned writings, some speculate that not only ancient Chinese and Korean documents, but even texts in Hebrew might have existed.

Having seized power, Soga no Umako installed a series of emperors (tennō) who were essentially his protégés, never appearing on the front stage himself, yet maintaining political authority behind the scenes. Remarkably long-lived for his era, Soga no Umako wielded power for 54 years, during which the Buddhist (effectively Sinicized) transformation of Japan accelerated rapidly.

If we consider the previous historical narrative as that of the Mononobe clan, then to overwrite that perspective, in 620 Soga no Umako began compiling new historical documents. These consisted of two texts: the Kokki and the Tennōki.

While the latter (Tennōki) was burned during the coup d’état of 645 that aimed to topple the Soga clan’s regime, the former (Kokki) was rescued and offered to Emperor Tenchi (r. 668–672), who managed and oversaw it thereafter.

The Kokki compiled ancient traditions from various regions. Its significance grew under the reign of Emperor Tenmu (r. 673–686), who was Emperor Tenchi’s younger brother and also took the throne himself.

During Emperor Tenmu’s reign, efforts were made to break free from the “historical view of the Soga clan” embedded in the Kokki, leading to the compilation of a new official history under his imperial decree.

It is crucial to note that Emperor Tenmu’s approach to compiling the new history did not assume textualization. Instead, it relied on the oral recitation of a person named Hieda no Are.

Why did Emperor Tenmu reject the conventional method of textual documentation and choose this method of oral transmission?

It was because the texts created to establish the “historical view of the Soga clan” were naturally composed in Chinese, the language of dominant international influence at the time. One key figure involved in producing these history-writing projects, in fact serving as a de facto mentor, was Prince Shōtoku (574–622).

Prince Shōtoku was the central figure in promoting Buddhism and simultaneously the primary architect of Sinicization. With the Soga clan in power, he secured key positions and, through the triangle of “Emperor–Soga no Umako–Prince Shōtoku,” China-oriented Buddhist reform advanced at great speed.

Prince Shōtoku strongly advocated strengthening ties with the Sui Dynasty, dispatching emissaries to Sui China, building temples, establishing Japan’s first official rank system (the Twelve Level Cap and Rank System), and drafting Japan’s first constitution (the Seventeen-Article Constitution), all under Chinese influence.

As political regimes change, so do their governing principles. Under Emperor Tenmu, now opposed to the Soga faction (which had become the old guard), the strategy to break free from their influence included “de-Sinicization” of the historical narrative.

However, Japan at the time did not have a fully developed alternative written language to counter the dominance of Chinese characters.

Naturally, foreign circumstances also played a role. When the Soga clan reigned, China underwent a transition from Sui to Tang, while on the Korean peninsula, the kingdom of Silla succeeded in repelling Tang China and unifying the peninsula. These geopolitical shifts influenced Japan’s cultural and political strategies as well.

Emperor Tenmu, unable to entirely detach from Chinese characters, chose to revert to a non-textual mode of transmission—oral recitation. Yet later, under Empress Genmei (r. 707–715), concerns arose that this historical perspective might be lost over time. She promptly ordered that part of the ancient traditions orally transmitted by Hieda no Are be committed to writing. The result of this effort was the Kojiki.

In the ongoing process of erasing old histories and rewriting them into new ones, the chaotic historical reality of multiple ethnic groups mingling throughout western Japan was erased. This erasure lies at the heart of the perplexing question: what is Japan, and who are the Japanese?

The Kojiki’s compilation was an attempt at “de-Sinicization.” And so my journey to understand Japan began there.